June 1st, 2025

Under the Feather welcomes one of the Alaska Raptor Center’s Avian Care Specialist, Savanna Hartman as guest blogger! Originally from North Carolina, Savanna earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Pre-Veterinary Medicine with a minor in wildlife rehabilitation from Lees-McRae College. If you asked her what her favorite bird is, the answer would be red-tailed hawks and to say that Savanna has a passion for these beautiful birds would be an understatement! This is her second summer working with the ambassador birds at the ARC.

Species Spotlight: Red-Tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis)

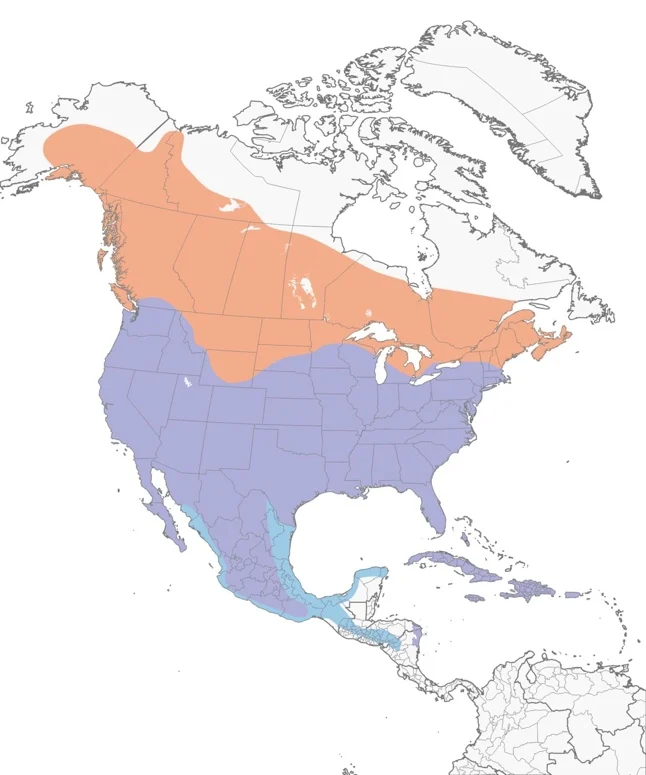

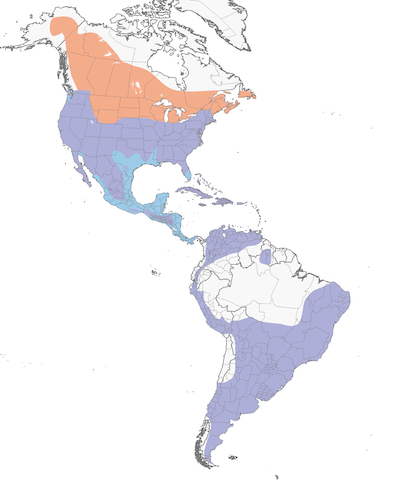

Adaptable. Beautiful. Some might even say perfect. The red-tailed hawk is a stunning North American raptor that can be found across most of the continent. A common “road trip raptor”, they are often seen perched along the roadside on trees or power lines. The adults are easily identifiable by their blazing red tails, making these birds a favorite for beginner and experienced birdwatchers. Among the most numerous raptors in North America, they are nevertheless a wonder to see each and every time.

I received my introduction to Red-tailed hawks through falconry where their power and agility chasing squirrels through the trees made me lifelong fan. They are fairly large birds, with wingspans ranging from 44.9 to 52.4 inches (1.14 to 1.33 meters), but that doesn’t stop them from whipping around trees or crashing through brush after capturing a meal. As with most raptors, females are larger and heavier than their male counterparts. A male will usually weigh from 1.5 to 2.9 pounds (690 to 1300 grams) while a female averages 2 to 3.2 pounds (900 to 1460 grams). Primarily eaters of small mammals, they are very opportunistic and will also eat birds and small reptiles. Their diet largely depends on the region they live and what prey is available for them to hunt. They are adaptable hunters, taking prey as small as a mouse or as large as a jackrabbit, to everything in between including voles, squirrels, lizards, rats, and starlings.

I received my introduction to Red-tailed hawks through falconry where their power and agility chasing squirrels through the trees made me lifelong fan. They are fairly large birds, with wingspans ranging from 44.9 to 52.4 inches (1.14 to 1.33 meters), but that doesn’t stop them from whipping around trees or crashing through brush after capturing a meal. As with most raptors, females are larger and heavier than their male counterparts. A male will usually weigh from 1.5 to 2.9 pounds (690 to 1300 grams) while a female averages 2 to 3.2 pounds (900 to 1460 grams). Primarily eaters of small mammals, they are very opportunistic and will also eat birds and small reptiles. Their diet largely depends on the region they live and what prey is available for them to hunt. They are adaptable hunters, taking prey as small as a mouse or as large as a jackrabbit, to everything in between including voles, squirrels, lizards, rats, and starlings.

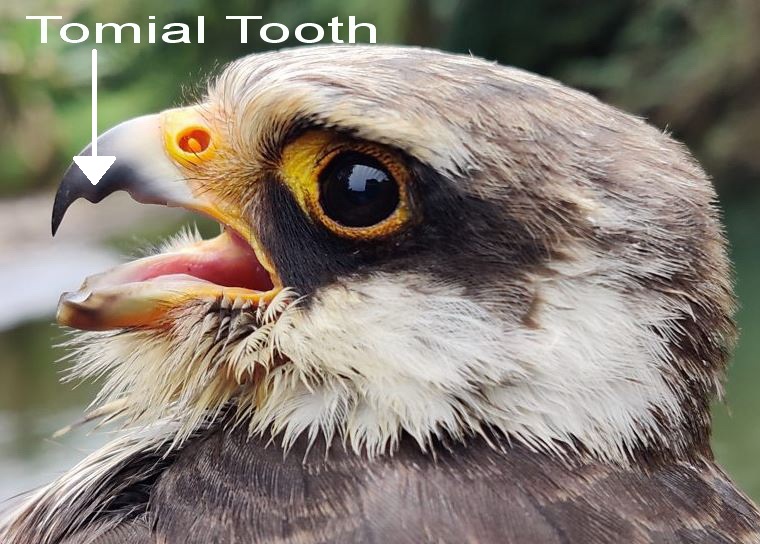

Red-tailed hawks are diurnal, meaning they are active and hunt during the day. They frequent open areas and are often seen perched on fences, trees, or telephone poles along the side of roads looking for a meal. When not perched their broad wings allow them to take advantage of thermal air currents to soar effortlessly through the sky. In addition, their keen sense of sight allows them to pick out possible prey from high vantage points. To identify a red-tailed hawk in flight, look for the broad round shape of its wings along with a short orange/red tail. Be careful! Only adults will have a red tail, juveniles will have a brown banded tail instead. With their wings extended in flight, a dark brown top with a white streaky underbelly and a dark bar near the wrist are identifiable physical markers. While this is the usual coloration for a red-tailed hawk, there is incredible regional diversity in the population.

Adult red-tailed hawks will have dark eyes and a red tail while juvenile red-tailed hawks have light golden colored eyes and a brown banded tail.

There are up to 16 subspecies of red-tailed hawks recognized throughout North and Central America. Two of these color variants were once thought to be separate species and are referred to by their more common names, Krider’s and Harlan’s red-tailed hawks. Krider’s hawks, found mainly in the Great Plains region of North America, have a pale body with an almost white head, little to no visible belly band and tails that are a washed out, with an almost pinkish coloration. Harlan’s hawks can be found in Alaska, and northwest Canada. Unlike the Krider’s, Harlan’s hawks have two distinct color morphs, dark and light. Dark morph Harlan’s are an overall chocolaty brown color while light morph Harlan’s are similar to the Krider’s. A light morph Harlan’s will have a pale body but the tail will be a darker red streaked with gray and brown.

The difference in coloration of an eastern red-tailed hawk (left) compared to a Krider’s (middle) and Harlan’s (right) red-tailed hawks.

Although their populations are not threatened, red-tailed hawks still face human related challenges. Electrocution, habitat loss, collisions and rodenticides are just a few of the threats to these large hawks. Due to their habits of hunting near roadsides, car collisions are one of the most common types of injuries that bring red-tailed hawks into rehabilitation. One thing we can do to help minimize this risk is to refrain from throwing any trash out of our cars as we drive. Yes, this includes biodegradable things like banana peels or apple cores! Those food scraps bring rodents to the side of the road and put raptors in danger of being struck as they hunt for dinner.

The Alaska Raptor Center currently has three resident red-tailed hawks, Edie, Jake, and Koyu. All three came into rehabilitation due to human related causes and now represent their species as educators after being evaluated as non-releasable. They also all look nothing alike! Edie is from Texas and is the typical eastern red-tail coloration. Jake, we believe, is half western red-tail half Harlan’s red-tail, and Koyu is a rare light morph Harlan’s red-tailed hawk. You can find out more about each of them on our Adopt-a-Raptor page of the website at https://alaskaraptor.org/adopt-a-raptor/

To learn more about red-tailed hawks, the research being done and view all the subspecies colorations, visit the Red-tailed Hawk Project at https://redtailedhawkproject.org/

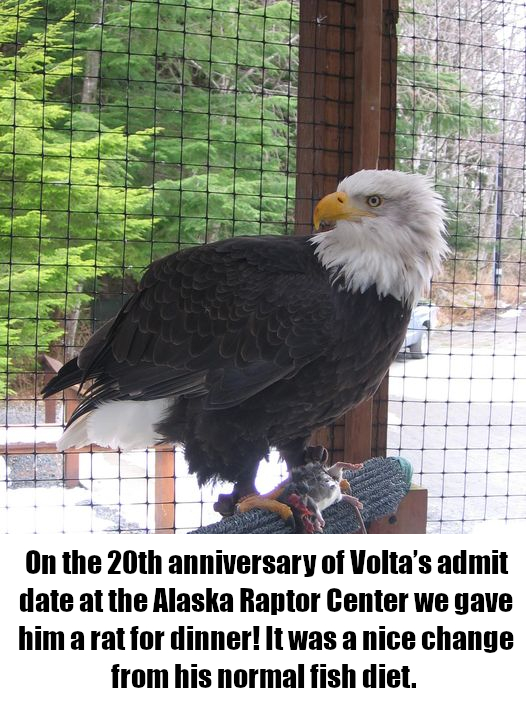

January and February also brought some losses to our avian ambassador team. Two days into the New Year we lost one of our Bald Eagles, Volta. He was such an amazing bald eagle and was one of the very first eagles that I worked with at ARC in 1995. Volta had been with the ARC since he was injured in 1992. He was an adult when he was injured, so we had no way of knowing his actual age. We do know that he was at least 37; although I have a feeling he was a bit older than that. Volta took a piece of my heart when he left us. He was quite a special bird to many.

January and February also brought some losses to our avian ambassador team. Two days into the New Year we lost one of our Bald Eagles, Volta. He was such an amazing bald eagle and was one of the very first eagles that I worked with at ARC in 1995. Volta had been with the ARC since he was injured in 1992. He was an adult when he was injured, so we had no way of knowing his actual age. We do know that he was at least 37; although I have a feeling he was a bit older than that. Volta took a piece of my heart when he left us. He was quite a special bird to many. In addition, we also lost two of our smaller ambassadors; Tootsie, a Northern Saw-whet Owl and Peanut, a Western Screech-Owl. Both of these small owls had lived longer than the average lifespan of their species. They both started having medical issues associated with old age and we had to make the hard decision to let them go. We don’t want our birds living in unnecessary pain. While we were never able to release them back into the wild, we were able to give them a release from their pain.

In addition, we also lost two of our smaller ambassadors; Tootsie, a Northern Saw-whet Owl and Peanut, a Western Screech-Owl. Both of these small owls had lived longer than the average lifespan of their species. They both started having medical issues associated with old age and we had to make the hard decision to let them go. We don’t want our birds living in unnecessary pain. While we were never able to release them back into the wild, we were able to give them a release from their pain. The end of July brought us good news and bad. After an intensive search, the ARC Board of Directors hired a new Executive Director, Carol Bryant-Martin from Tallahassee, Florida. It was wonderful to get some leadership back at the Center. She is still learning all the ins and outs of the ARC, but things are coming along! We are looking forward to continuing plans for the future developments and big changes to come! Unfortunately, July also brought the loss of one more avian ambassador, a Great Horned Owl named Owlison. She had been in human care for a number of years before coming to the ARC in 2014. She had developed terrible arthritis in her hips and her back. Again, we made the difficult choice to relieve her of that pain.

The end of July brought us good news and bad. After an intensive search, the ARC Board of Directors hired a new Executive Director, Carol Bryant-Martin from Tallahassee, Florida. It was wonderful to get some leadership back at the Center. She is still learning all the ins and outs of the ARC, but things are coming along! We are looking forward to continuing plans for the future developments and big changes to come! Unfortunately, July also brought the loss of one more avian ambassador, a Great Horned Owl named Owlison. She had been in human care for a number of years before coming to the ARC in 2014. She had developed terrible arthritis in her hips and her back. Again, we made the difficult choice to relieve her of that pain. We were able to finally move birds into some new enclosures by mid-August. We have a wonderful new building that can house four ambassador birds. Each mew was designed to have an inside space and an outside space. This gives the birds the freedom to choose whether they want to be exposed to the elements and enjoy a view of the woods or move to the back part of the enclosure and be out of the weather or away from things that make them uneasy. They seem to spend most of the time in the front, watching what is going on around them. The ARC team is always working towards improving the quality of life for our avian ambassadors. We are grateful for the support from our members and donors to be able to provide the birds with a more natural environment and allow them to take in the world around them.

We were able to finally move birds into some new enclosures by mid-August. We have a wonderful new building that can house four ambassador birds. Each mew was designed to have an inside space and an outside space. This gives the birds the freedom to choose whether they want to be exposed to the elements and enjoy a view of the woods or move to the back part of the enclosure and be out of the weather or away from things that make them uneasy. They seem to spend most of the time in the front, watching what is going on around them. The ARC team is always working towards improving the quality of life for our avian ambassadors. We are grateful for the support from our members and donors to be able to provide the birds with a more natural environment and allow them to take in the world around them. The positives just kept coming! Earlier in the summer we admitted a fuzzy bald eagle chick. This was one of the youngest eaglets we had ever admitted. Staff estimated her age to be around 4 weeks old. Her rescuer named the tiny chick Via. ARC avian staff spent the summer making sure that she was getting fed plenty of high quality fish and rats to help her grow. A beautiful makeshift nest was built and she was placed in the nest, along with a stuffed eagle. Housing her in the flight allowed her to see the other eagles, watch their behaviors, and be exposed to the proper amount of light and weather to help her grow. Via is now flying with those eagles and will be released in the spring when the herring are spawning!

The positives just kept coming! Earlier in the summer we admitted a fuzzy bald eagle chick. This was one of the youngest eaglets we had ever admitted. Staff estimated her age to be around 4 weeks old. Her rescuer named the tiny chick Via. ARC avian staff spent the summer making sure that she was getting fed plenty of high quality fish and rats to help her grow. A beautiful makeshift nest was built and she was placed in the nest, along with a stuffed eagle. Housing her in the flight allowed her to see the other eagles, watch their behaviors, and be exposed to the proper amount of light and weather to help her grow. Via is now flying with those eagles and will be released in the spring when the herring are spawning! get many as patients, even though they are common in southeastern Alaska. Over the years, we have never successfully rehabilitated a merlin to the point of release. They are small falcons and tend to get themselves into trouble by hitting windows or wires and badly injuring their wings. This merlin (named Wizard by the rescuer) had done just that, hit a window while hunting for birds. He ended up with a broken ulna, one of the bones in his wing. We handled him with kid gloves, hoping to not make things worse! A lot of cage rest and then some time building back his strength allowed the bone to heal and we were finally able to release him! It was a huge accomplishment for all the avian staff at the ARC!

get many as patients, even though they are common in southeastern Alaska. Over the years, we have never successfully rehabilitated a merlin to the point of release. They are small falcons and tend to get themselves into trouble by hitting windows or wires and badly injuring their wings. This merlin (named Wizard by the rescuer) had done just that, hit a window while hunting for birds. He ended up with a broken ulna, one of the bones in his wing. We handled him with kid gloves, hoping to not make things worse! A lot of cage rest and then some time building back his strength allowed the bone to heal and we were finally able to release him! It was a huge accomplishment for all the avian staff at the ARC! The year 2024 was nearing the end, but before that happened, ARC added two new avian ambassadors to the team! We added a beautiful barred owl that had been hit by a car in Ketchikan and broke her wingtip. She was named Varia. While she does have the ability to fly, she makes a lot of noise when doing so and since owls rely on their ability to fly silently in order to catch prey and we felt Varia would not be successful if released. The second bird is a retired falconry bird named Sable. Sable was bred in captivity and is a mix of a gyrfalcon and a peregrine falcon. She was trained and participated in hunting for 15 years by her breeder in Washington. While she no longer hunts, she is a very healthy bird and still has many years ahead of her, educating visitors about falcons and falconry. We are privileged to be able to give her a home in her retirement years.

The year 2024 was nearing the end, but before that happened, ARC added two new avian ambassadors to the team! We added a beautiful barred owl that had been hit by a car in Ketchikan and broke her wingtip. She was named Varia. While she does have the ability to fly, she makes a lot of noise when doing so and since owls rely on their ability to fly silently in order to catch prey and we felt Varia would not be successful if released. The second bird is a retired falconry bird named Sable. Sable was bred in captivity and is a mix of a gyrfalcon and a peregrine falcon. She was trained and participated in hunting for 15 years by her breeder in Washington. While she no longer hunts, she is a very healthy bird and still has many years ahead of her, educating visitors about falcons and falconry. We are privileged to be able to give her a home in her retirement years.

needs of the birds and allows them opportunities to make choices. The enrichment offered helps to stimulate the senses, increase confidence in new environments, increase physical movement/exercise, support natural behaviors and reduce stress and boredom.

needs of the birds and allows them opportunities to make choices. The enrichment offered helps to stimulate the senses, increase confidence in new environments, increase physical movement/exercise, support natural behaviors and reduce stress and boredom.  Enrichment is usually broken down into five different categories; cognitive (problem solving), sensory, food, environmental (changes to enclosure), and behavioral (training). We try to offer our birds something from each of these categories on a weekly basis. There is always a bit of trial and error and some birds just don’t enjoy every bit of enrichment that we give them. That’s what enrichment is all about, giving them the choice to interact or not interact.

Enrichment is usually broken down into five different categories; cognitive (problem solving), sensory, food, environmental (changes to enclosure), and behavioral (training). We try to offer our birds something from each of these categories on a weekly basis. There is always a bit of trial and error and some birds just don’t enjoy every bit of enrichment that we give them. That’s what enrichment is all about, giving them the choice to interact or not interact.

For me, the best part of giving enrichment to the birds is watching them interact with it. I always leave with a huge grin on my face when one of the birds is really into figuring out or destroying the enrichment given to them. I know that our birds are healthy, mental stimulated and it seems like, enjoying the interaction!

For me, the best part of giving enrichment to the birds is watching them interact with it. I always leave with a huge grin on my face when one of the birds is really into figuring out or destroying the enrichment given to them. I know that our birds are healthy, mental stimulated and it seems like, enjoying the interaction!